A STORY BY NASEER

The shoebox wasn’t labeled, which meant it was the important one.

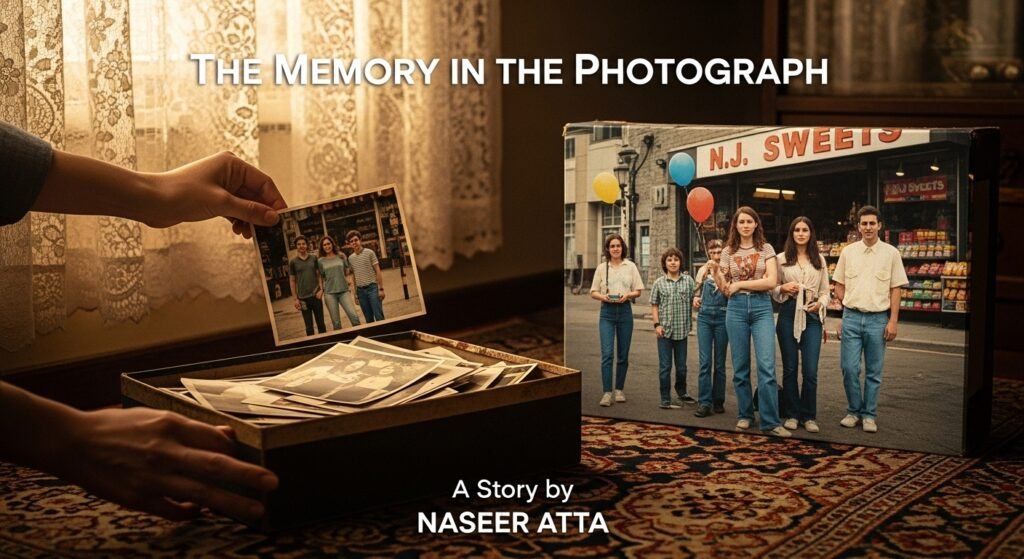

Mara found it at the back of the wardrobe while helping her grandmother sort through winter shawls. The box smelled faintly of camphor and sandalwood. Inside it, rubber-banded stacks of pictures, and a lone photograph of her parents, edges soft from years of being thumbed and told about.

“Careful,” Granny said from the bed. Her voice was thin but amused. “Those are the loud ones.”

“Loud?”

“They shout at you until you listen.”

Mara smiled and sat cross-legged on the rug. There were weddings and birthdays and the kind of pictures where the photographer clearly told everyone to say “cheese,” and nobody knew what to do with their hands. And then she found a glossy print with a pale border, the colors just a little washed by time.

Four people at a park on what looked like a monsoon afternoon: her grandfather, looking awkward in a too-stiff shirt; granny, young and bright-eyed; Mara’s mother as a child, holding a red balloon; and—at the very edge, half-caught as if trying to leave the frame—a woman Mara didn’t recognize. Blue jeans and a t-shirt, hair pinned loosely, a silver bangle flashing at her wrist. She wasn’t looking at the camera. She was looking at Granny.

“Granny,” Mara said, bringing the photograph closer, “who’s this?”

She took the picture with both hands, just as she held prayer beads. For a moment, she didn’t speak—the room filled with the quiet tick of the wall clock.

“That,” she said softly, “is Clara.”

Mara waited. Granny traced the corner of the print, her finger hovering over the blue of Clara’s sleeve.

“We were neighbors,” she said. “Schoolgirls. We used to skip tuitions and sit on the roof with guavas and salt. She’d tell me the names of clouds. She always knew the right words.”

“Where is she now?”

“I don’t know.”

“How can you not know?”

“Because we stopped speaking,” Granny said, and the words landed like a small, careful stone.

Granny glanced back at the photo. There was more to it than faces. In the background, a bakery sign—NJ Sweets—hung crooked above a tin shutter. A small boy in gumboots splashed through a puddle. The balloon string in her mother’s hand pulled just slightly, caught by the wind. None of it was posed. All of it felt true.

“What happened?”

Granny’s mouth tilted, not quite a smile. “Life. I married early. Her family moved to another part of the city. Letters at first… then fewer. And then something foolish.”

“What?”

“I didn’t show up,” she said. “She invited me to her marriage ceremony. Your grandfather had just started his job. His mother didn’t approve of… many things. I thought I would make peace by staying home. I told myself there would be time later to explain.” She touched the edge of the photo. “There wasn’t.”

Mara sat back. The idea of granny—her tidy, steady granny—missing something like that felt wrong. But the longer she looked, the more the picture showed. It wasn’t only who was in the frame; it was who had taken it, who had run toward the balloon, who had blinked and missed a moment and never got it back.

“Do you want to find her?” Mara asked.

“After all this time?” She looked toward the window, where the afternoon light thinned into gray. “I don’t know what I would say.”

“Maybe you don’t have to know. Maybe you just have to ask.”

She laughed softly. “You always were stubborn.”

Mara turned the photo over. In blue ink, neat and slanted: NJ Park, July 1998. And a studio stamp in purple: NJ Photo Works, Tower Market.

The next day, Mara took the print and a bus to Tower Market. The photo studio was still there, squeezed between a shop that sold school bags and another that sold pens that promised never to run out. Inside, cameras hung like patient bats. An old man with kind eyes polished a lens with a square of cotton.

“NJ Owner?” She asked.

“His son,” he said, smiling. “But I answer to the name.”

She placed the photo on the counter. “My grandfather used to bring films here. Do you know anything about where this was taken?”

He peered at it, then nodded. “NJ Park is gone,” he said. “They built apartments. But NJ Sweets moved to the next lane. Same family.” He squinted at the woman in blue. “And this bangle! My mother sold those in the market. Everyone wore them.”

“Do you recognize her?”

He shook his head gently. “Faces you don’t name fade into crowds. But check the bakery. Old men remember better than pictures.”

Mara thanked him and followed the map in her phone and the map of memory in the photograph. NJ Sweets smelled like butter and sugar. Behind the counter, a man with a white mustache arranged Jalebi into spirals.

“Uncle,” she said, holding out the picture. “Do you know this place?”

He laughed. “I know that balloon,” he said. “We gave those free with ice cream in ‘98. Children cried when they flew away.” He tapped the sign, newer now, not crooked. “The shop is mine. The park is not.”

“And the woman?”

He squinted. “Looks like… Clara? Lived three streets down. Used to come for bread on credit and pay with sweets on celebrations.” He rubbed his mustache, thinking. “She married a clerk, moved to Karachi. Her mother kept her letters in a tin. When the mother passed, the letters went somewhere. Maybe to a cousin.”

Mara walked home with a paper bag of bread and a head buzzing with thread ends. At dinner, she told Granny what she’d learned. Granny listened, fingers still on her spoon.

“I thought it would hurt to hear her name,” she said. “It doesn’t. It’s like opening a window.”

That night, Mara messaged a cousin who seemed to know everyone’s business and posted to a neighborhood Facebook group. She wrote: ‘Looking for Clara, married around 1999, moved to Karachi. Friend of Sarrah (my grandmother).’ She attached the photo, the blue sleeve, and the silver bangle.

She waited.

The reply came two days later, from a woman named Sarrah—another Sarrah, not her granny. ‘I think you are looking for my mother,’ the message read. ‘Her name was Clara. She passed away in 2017. I have some of her things. Who are you?’

Mara stared at the screen for a long minute, then typed: ‘I’m the granddaughter of her friend.’

They arranged tea on a Sunday.

Sarrah lived in a small apartment on the third floor of a building that smelled of floor cleaner and cardamom. She had her mother’s eyes, laughter that arrived quickly and left slowly. On the coffee table, she placed a tin painted with flowers.

“I kept this,” she said, opening it. Inside were letters tied with ribbon, a dried marigold, and a bus ticket from a city Mara had never visited. “She didn’t talk much about old friends. Only once, when the rain came hard, she said she missed the girl who knew the names of clouds.”

Granny’s hand trembled as she lifted a letter. The paper had the faintest scent of rose and dust. The handwriting was big and round.

‘Dear Sarrah,’ the letter began, and Mara blinked. Not to her granny. To this Sarrah, the daughter. She glanced up.

“She wrote to me sometimes,” Sarrah said. “All the things she didn’t say out loud, she wrote. Look.”

She handed another letter to Granny. This one was older, the edges curled. ‘Dear Anna,’ it began—Granny’s name before everyone called her by her honorific. Mara watched as Granny’s face changed. Not pain, exactly. Something like release.

“I was angry you didn’t come,” the letter said. “But when the rain started, I thought of our roof and the guavas and the way you always licked the salt off your fingers first. The hope that you are happy and loved kept me going. I’m keeping a chair for you whenever you are ready.”

Granny pressed the paper to her chest. “I thought I had lost the right to remember,” she whispered. “But she kept a chair.”

Sarrah set two cups of tea in front of them. “I kept the chair,” she said, smiling. “It squeaks.”

They talked until the light faded. Traded recipes and the story of the red balloon, and the way the old studio owner still polished lenses like prayer. They took a new photograph on Mara’s phone—three women across time, the tin between them, and the past invited to sit.

On the way home, Mara held the original print again. It looked different now, though nothing on its surface had changed. The woman at the edge of the frame was no longer a stranger.

At the flat, Granny stood in the doorway with her shawl wrapped tight. “Well?” she asked, eyes bright as a girl’s.

Mara slipped the photograph into Granny’s hands. “She kept a chair,” she said.

Granny laughed, and in the sound Mara heard rain on a roof, and a sky full of cloud names.

Later, she took a pen and wrote on the back of the photograph, beneath the studio stamp: NJ Park, July 1998. Sarrah, finally found. She slid it back into the shoebox with the others.

Some memories shout. Others wait quietly inside a picture until you’re ready to hear them.

This one did both.

Love this story? Read more.